Power in Action

How Principles Survive Contact with Power

Part II of “The Prince and the Emperor” - read Part I here.

In 165 CE, as the Antonine Plague began ravaging the Roman Empire, Marcus Aurelius faced decisions that would test his philosophical principles and practical effectiveness. The most powerful man in the world, who wrote about accepting fate and maintaining equilibrium, now had to actually do it – not in the quiet of his study, but in the crucible of crisis.

This wasn't a philosophical exercise. People were dying. The empire's economy was straining. Military campaigns were compromised. Every decision the emperor made would ripple worldwide, affecting millions of lives.

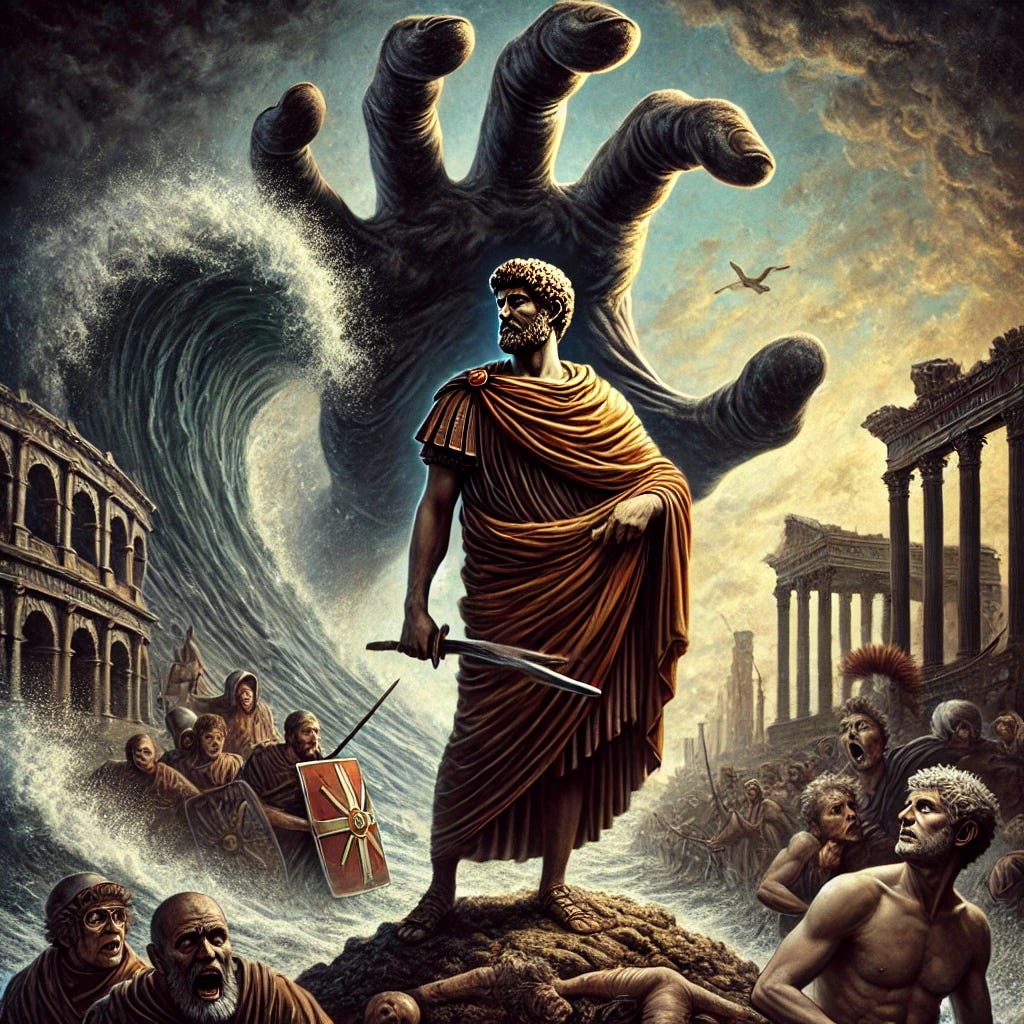

What makes this moment remarkable isn't just that Marcus Aurelius wielded power effectively – it's that he did so with unwavering resilience, maintaining the philosophical principles he wrote about in his private meditations. When he wrote that a leader must "be like the rocky headland on which the waves constantly break," he wasn't engaging in comfortable theorizing. He was describing what he actually did when facing empire-shaking crises.

This is where we begin to understand the true mastery of power: not in philosophical detachment alone, nor in pure pragmatism, but in the lived reality of wielding power with both wisdom and effectiveness. The contrast between Marcus Aurelius and figures like Cesare Borgia – both masters of power in their own way – reveals something profound about the relationship between principles and effectiveness.

When Philosophy Meets Crisis

The Antonine Plague presented Marcus Aurelius with a unique and daunting set of challenges. The disease, likely smallpox, was killing up to one-third of the population in some areas. The empire's armies, crucial for maintaining borders and suppressing revolts, were being decimated. Trade was disrupted, threatening food supplies to major cities.

Each decision point forced Marcus to balance his Stoic principles with practical necessities:

When advisers suggested closing Rome's ports to prevent disease spread, potentially saving thousands of lives but certainly causing economic devastation and food shortages, Marcus had to navigate between public health and economic survival.

When military commanders demanded to abandon frontier positions due to plague losses, risking barbarian incursions but potentially saving remaining troops, he had to balance strategic necessity with imperial security.

When wealthy senators fled Rome, threatening social stability but exercising what he had written was their natural right to self-preservation, he had to reconcile individual liberty with collective responsibility.

What's remarkable isn't just that Marcus handled these challenges effectively – though he did, keeping the empire stable through the crisis. What's truly extraordinary is how he maintained his philosophical principles. He didn't just survive the crisis; he demonstrated that principles could guide effective action even under extreme pressure.

The Raw Edge of Power

Contrast this with Cesare Borgia at Sinigaglia in 1502. Borgia, whom Machiavelli would later praise as a master of virtú, faced his own crucial moment. His enemies, a group of rebellious condottieri (mercenary leaders), had become a threat to his power. His solution was brilliant and brutal: invite them to Sinigaglia for reconciliation, then trap and execute them.

The scheme worked perfectly. In a single stroke, Borgia eliminated his opponents and consolidated his power. Machiavelli, who witnessed the aftermath, was impressed by the sheer effectiveness of the operation. Here was power wielded with absolute precision and zero hesitation.

But there's a crucial difference between Borgia's mastery of power and Marcus Aurelius's. Borgia's power was raw, untempered by principle. It worked – until it didn't. When his father, Pope Alexander VI, died and his health failed, Borgia's power structure collapsed. He had built everything on pragmatic effectiveness without the foundation of principle, and in the end, he lost everything.

The Price of Unprincipled Power

This contrast reveals something profound about the nature of power. Marcus Aurelius, facing an empire-wide plague that killed millions and threatened everything he ruled, maintained his principles and effectiveness. He made hard decisions but always with philosophical wisdom that considered the greater good and long-term consequences.

Borgia, meanwhile, achieved spectacular short-term success through pure pragmatism. His actions at Sinigaglia were a masterclass in tactical brilliance. But without a foundation of principle, his power proved brittle. When fortune turned against him, he had no deeper reserves to draw upon.

The Living Synthesis

The lessons here aren't just historical. They speak directly to how power should be wielded in any era:

Principles aren't a constraint on power – they're a foundation for effective use. Marcus Aurelius's philosophical framework didn't prevent him from taking necessary action; it helped him take the right actions for the right reasons.

While potentially effective in the short term, pure pragmatism creates brittle power structures. Borgia's fall wasn't just bad luck but the inevitable result of power without principle, a stark reminder of the long-term consequences of such an approach.

True virtú isn't just about effectiveness but principled effectiveness. Marcus Aurelius demonstrated that you can maintain your principles while taking decisive action and that principles actually make your actions more effective in the long run.

Modern Implications

Today's leaders face their own plagues, their own Sinigaglias. They must make decisions that balance immediate effectiveness with long-term consequences and pragmatic necessity with ethical principles. The examples of Marcus Aurelius and Cesare Borgia offer two contrasting models:

The path of principled power: harder in the moment, but creating lasting positive impact

The path of pure pragmatism: potentially effective in the short term but ultimately unsustainable

The choice between these paths isn't just philosophical – it's practical. Marcus Aurelius's empire survived crisis after crisis, holding together even after his death. Borgia's carefully constructed power base collapsed almost immediately when circumstances turned against him.

The True Nature of Power

Ultimately, these historical examples reveal that true power – lasting, effective, meaningful power – comes not from pragmatism alone but pragmatism guided by principle. Marcus Aurelius wasn't just a philosopher who happened to be emperor; he was a better emperor because he was a philosopher. His principles didn't handicap his exercise of power – they enhanced it.

This is the most important lesson for modern leaders: principles aren't a luxury to be discarded in crisis but the foundation that makes effective action possible. The goal isn't to choose between being principled and being effective but to achieve both – to be, like Marcus Aurelius, a leader whose principles make them more effective, not less.

The truest test of leadership isn't just achieving immediate results but achieving them in a way that builds rather than undermines the foundation for future success. In this, Marcus Aurelius remains our best teacher – not despite his principles, but because of them.